Hiring: The 2025 Public Sector Talent Race: Who’s Winning, Who’s Chasing

There’s no hiding it—I’m a data nerd.

I love connecting macro trends to the real conversations I have with my public sector network. I’m also fully invested in the AI industrial revolution (even if it occasionally threatens to devalue my own skillset!).

This time, I took it a step further. I partnered with AI to supercharge my search for insights. Combining AI-powered research, the latest public sector workforce data, and my relentless demands for “More! MORE! MOOOOORE!”, until we built a picture of how each jurisdiction (APS, QLD, NSW, VIC) is stacking up.

Are the insights perfect? No. Some regions lack updated data, and AI isn’t flawless. But we’ve uncovered highlights powerful trends, emerging gaps, and fresh perspectives—without human bias on my part.

It’s a chunky read, but it’s worth it. I’ve structured it to give you the big picture first, followed by AI’s jurisdiction-by-jurisdiction deep dive across key metrics and common themes.

The Crux of It

To summarise my AI-sidekick’s efforts, while each government jurisdiction faces unique circumstances – Queensland expanding services, NSW improving processes, Victoria tightening belts, and the APS reforming workforce management – they all grapple with common themes in talent acquisition: attracting scarce skills, speeding up recruitment, and retaining a capable, diverse workforce in a competitive labour market. Public sector employers are increasingly adopting private-sector strategies (improving branding, offering flexibility, using data to inform workforce plans) while also leveraging their public-purpose appeal. The coming year will test their ability to adapt and maintain performance amid economic and political pressures, but the ongoing sharing of best practices and data (through state workforce reports and auditor reviews) bodes well for continuous improvement in public sector talent outcomes.

The 2025 Public Sector Talent Race: Who’s Winning, Who’s Chasing?

The Australian public sector – spanning the Australian Government and state governments like Queensland, New South Wales, and Victoria – faces a tight labour market and evolving workforce needs. This comparative analysis presents current (2024–2025) data on talent acquisition and workforce outcomes in these jurisdictions. Key performance indicators include recruitment success rates (time-to-hire, fill rates, hard-to-fill roles), staff turnover, skills gaps, vacancy levels, and workforce growth or reduction. Where possible, contrasts are made between jurisdictions and against private-sector benchmarks for context. The analysis also notes niche talent trends (e.g. digital skills, STEM roles, First Nations employment) and differences in workforce planning, employer branding, and employment offers.

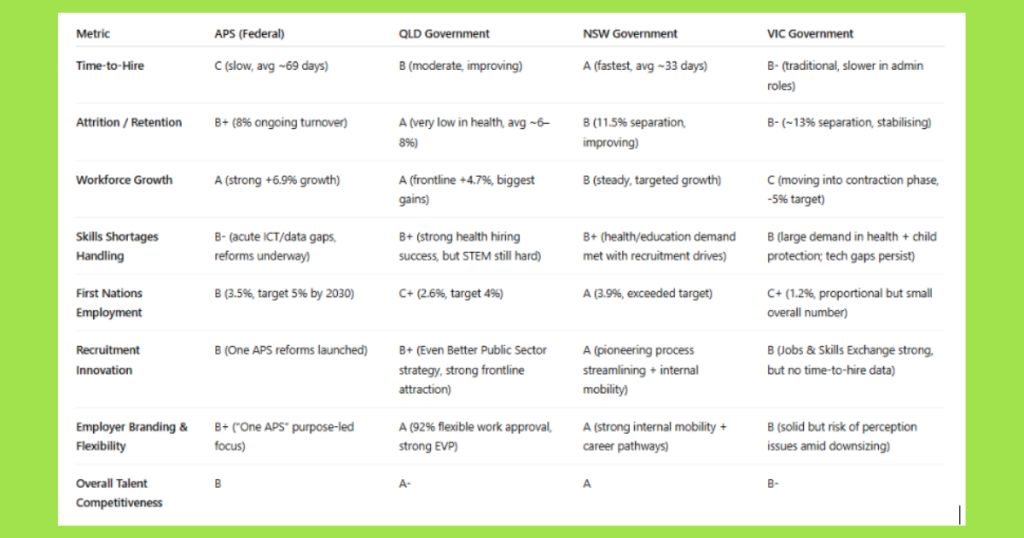

Figure1: The 2025 Public Sector Talent Scorecard

A = Leading practice, B = Strong, but with some gaps, C = Under pressure or clear improvement needed

Comparative Insights

- Time-to-Hire: Public sector hiring speeds differ across jurisdictions, with the APS historically slower than the states. The Australian Government’s ~69 day hiring cycle in large agenciesapsc.gov.au significantly lags the ~33–39 day averages reported in NSW and the private sectorapsc.gov.au. NSW has set a benchmark by cutting its average recruitment time to just 33 dayspsc.nsw.gov.au, nearly matching private companies (the Australian HR Institute reports 33 days as the private-sector average for 2022–23)apsc.gov.au. Queensland and Victoria have not published comparable figures, but indications are Qld’s hiring times are moderate (some health roles are filled within weeks given continuous recruiting), whereas Victoria’s might be longer in administrative areas due to traditional processes. Overall, private-sector employers often move faster in recruitment, which pressures public agencies – hence the reforms in APS and NSW to speed up hiring so they don’t lose talent to quicker offersapsc.gov.au.

- Turnover Rates: In terms of attrition, public sector turnover is generally comparable to or slightly lower than the private sector average. The average annual employee turnover in Australia was ~14% in 2023 across all industriesahri.com.au. Public sector figures: NSW at 11.5% (2023)psc.nsw.gov.au, Victoria roughly ~13%, Queensland Health ~6–7% (with broader Qld likely in the ~8–10% range for stable departments), and the APS around 8% for ongoing staff in 2022–23 (up from ~7% pre-pandemic). This suggests public sector jobs often have marginally higher retention than private, likely due to job security and benefits, but the difference is not large. Notably, healthcare roles have bifurcated outcomes: Queensland’s health workforce attrition (~6%)statements.qld.gov.au is much lower than New South Wales Health’s (~13%)statements.qld.gov.au, possibly reflecting differences in workload or pay strategies. High-stress public safety roles (police, child protection) show elevated turnover in many jurisdictions (e.g. Qld Police 10.7%abc.net.au, NSW Police 8.3% exitspsc.nsw.gov.au), yet still often below analogous private sector roles like security or call-centre jobs. Importantly, post-COVID “resignation” surges hit both sectors, but governments are seeing those stabilize nowpsc.nsw.gov.au. Maintaining lower turnover than private peers will likely hinge on public sectors leveraging their strengths – job stability, clear career progression (e.g. rank structures), and purpose-driven work – to retain staff even when private firms may offer higher pay.

- Workforce Growth vs Constraints: We see divergent trends: Queensland and the APS have been expanding their workforce (APS +6.9% in a yearapsc.gov.au, Qld +4.3% frontline FTEabc.net.au), whereas Victoria is now planning a workforce contraction of ~5%themandarin.com.au to rein in spending. New South Wales is somewhere in between – it expanded in key areas but is trying to contain costs and keep overall numbers steady around 10% of the labour forcepsc.nsw.gov.au. The private sector, by contrast, experienced slower job growth in 2023–24; remarkably, 87% of Australia’s net employment growth from Mar 2023 to Sep 2024 was in public-funded sectors (health, education, public administration)hcamag.com. This massive public hiring surge has propped up national employment, but also raised concerns about wage pressures and crowding out private hiringhcamag.comhcamag.com. From an employer perspective, the public sector’s growth means more competition for talent between governments and also with private businesses. For instance, when multiple states are simultaneously recruiting nurses overseas or vying for IT specialists in a city, it can drive up salary expectations. Private firms sometimes counter by offering higher pay or perks, while governments highlight job stability and public service impact. Going forward, if Victoria’s cuts proceed, it will buck the growth trend and could release some talent to the market (e.g. project managers or policy officers might move to other states or sectors), whereas the APS and Queensland will continue to absorb skilled workers. Each government must balance service needs with budget sustainability – a dynamic also seen in the private sector as companies hire or downsize based on economic conditions.

- Hard-to-Fill Roles and Skill Shortages: There is a common pattern across jurisdictions: digital, data, and STEM roles are hard to fill everywhere. Governments and private companies are fishing from the same pool of data scientists, software engineers, cybersecurity experts, and accountants. In the APS, as noted, 65% of agencies lack enough ICT/digital skillsapsc.gov.au, and states report similar struggles in tech recruitment. Private sector tech firms often offer higher salaries or equity, making it tough for public agencies to compete. As a result, we see public sectors innovating: the APS and NSW have digital talent pools and academies, Queensland is partnering with universities for bonded scholarships in tech, and Victoria has a Digital Fellows program. Another niche area is First Nations roles – here the issue is not a “skill shortage” per se but an underrepresentation challenge. NSW stands out as having made strong progress (3.9% Indigenous workforce)psc.nsw.gov.au, while Qld and Vic lag behind their targetspsc.qld.gov.auvpsc.vic.gov.au. The APS is putting emphasis on Indigenous employment as well, with long-term targetsapsc.gov.au. Culturally specific recruitment and support programs are being expanded to ensure the public sector attracts and retains First Nations employees (who are also sought after by corporates for diversity goals). In fields like healthcare and STEM teaching, shortages are widespread in both public and private (e.g. private hospitals and public hospitals compete for nurses; public schools and private schools both need science teachers). High-demand public sector roles like paramedics, social workers, town planners, and engineers see competition from private and nonprofit sectors. Governments are increasingly using targeted incentives – for example, Queensland offers rural teachers’ extra allowances, and NSW has sign-on bonuses for experienced nurses – similar to private-sector hiring bonuses.

- Employer Branding and Offers: Each jurisdiction has tailored its employment branding. Queensland emphasizes a supportive, purpose-driven workplace (“make a difference in the lives of Queenslanders”) and boasts high flexible work uptake (92% approval)psc.qld.gov.au, which is an attractive metric for candidates seeking work-life balance. NSW brands itself via “I Work for NSW”, highlighting the breadth of roles and impact at scale (e.g. mega infrastructure, nation-leading services). Victoria traditionally highlighted its value-based culture and inclusion (e.g. leading on LGBTQ+ inclusion and gender equity), though the narrative is now tempered by budget realities – messaging is shifting to productivity and innovation in service delivery. The APS leverages the idea of contributing to national policy and service, and is currently pushing a “One APS, bound by purpose” employer value proposition, while also promoting improvements in recruitment practices to shed the image of bureaucracy. All public employers continue to offer non-monetary benefits competitive with or exceeding the private sector: above-average superannuation contributions, generous leave (e.g. extended parental leave), salary packaging, and career stability. These are often cited in recruitment materials as key differentiators against private companies. Meanwhile, private sector employers in 2024–25 have leaned into higher salary growth (wages in some industries grew at their fastest pace in a decade) and perks like remote work, which narrows the gap. Public sector wage growth is more constrained by budgets and bargaining frameworks, though new agreements (e.g. Victoria’s latest VPS agreement, NSW’s pay rise for nurses and teachers) are trying to keep government salaries attractive. Ultimately, many candidates will weigh mission and stability (public sector strengths) versus pay and agility (private sector strengths). Public sectors that can also streamline hiring and offer career development may capture talent that values meaningful work and long-term career over immediate higher pay.

The Deeper Dive

Australian Government (APS)

The Australian Public Service (APS) has been expanding its workforce after a period of restraint, but it faces challenges in recruitment speed and skills shortages:

- Workforce Size and Growth: As of June 2023 the APS employed about 170,332 people, reflecting a 6.9% increase (net +11,041 staff) during 2022–23apsc.gov.au. This growth followed deliberate hiring to rebuild capacity (22,031 ongoing staff were engaged that year) and reverse previous staffing caps. Most new roles are in service delivery, policy, and other federal functions. Separations also rose slightly – 11,798 ongoing employees left in 2022–23 (around 8% turnover by ongoing headcount)apsc.gov.au.

- Recruitment Timeframes: APS recruitment processes are notably lengthy and fragmented. A review found in large APS agencies the average time from job advertisement to a merit-selected candidate was ~69 days, far slower than in other sectorsapsc.gov.au. (For comparison, the NSW public service averages 39 days and the private sector about 33 daysapsc.gov.au.) Over 65% of new APS hires surveyed felt hiring could improve in timeliness and communicationapsc.gov.au. The slow pace means federal agencies often lose top talent to faster-moving employersapsc.gov.au. In response, there is a push for a “One APS” approach to streamline and standardize recruitment across agenciesapsc.gov.au – for example, sharing merit pools and simplifying application processes – to reduce time-to-hire and improve the candidate experience.

- Internal vs External Hiring: The APS tends to recruit from within. Just over 53% of new APS hires already had prior APS experienceapsc.gov.au, and senior executive roles are “nearly always” filled via internal promotionapsc.gov.au. This practice can ensure knowledge retention, but it also poses risks: it limits external talent inflow and can reinforce Canberra-centric staffingapsc.gov.au. (Most APS jobs are advertised in Canberra, even when talent pools in Sydney, Melbourne, or Brisbane might be strongerapsc.gov.au.) Narrow sourcing practices mean the APS may miss out on candidates in other states and risk less diverse perspectivesapsc.gov.au. The APS Workforce Strategy 2025 highlights the need to broaden recruitment and reduce “insider” bias to attract critical skills nationallyapsc.gov.au.

- Attrition and Turnover: APS turnover has risen post-pandemic. After very low exits in 2020–21, the separation rate in 2021–22 spiked above pre-COVID levelsapsc.gov.au. Low unemployment nationwide has made retention harder – historically, APS attrition rises when the broader job market tightensapsc.gov.au. Recent data show turnover is highest among newer staff: those with under 2 years’ service had a 12.2% separation rate, roughly double the rate for 10–15 year veteransapsc.gov.au. Higher turnover is also seen at the extremes of classification – junior APS levels and the Senior Executive Serviceapsc.gov.au – and in certain regions (e.g. remote Northern Territory offices)apsc.gov.au. Many leavers cite higher pay elsewhere or lack of career progression as reasons for exitapsc.gov.au. The APS is responding by creating clearer career pathways and promoting flexible work locations (encouraging roles outside Canberra) to boost retentionapsc.gov.au.

- Skills Gaps and High-Demand Roles: Like other sectors, the APS faces acute skills shortages in digital and STEM fields. An APS agency survey reported 65% of agencies had ICT and digital skill shortages, 48% faced data analytics/research gaps, and 34% had shortages in accounting and financeapsc.gov.auapsc.gov.au. Cybersecurity, data engineering, and software development roles are particularly hard to fill, with projected growth above 25% nationally by 2026apsc.gov.au. Salary competition makes it tough for the APS to hire and keep these specialists – private-sector wages for in-demand tech and accounting roles have surged, outpacing APS pay scalesapsc.gov.au. Agencies also report difficulties recruiting for engineering, project management, legal, and HR positionsapsc.gov.au. The APS is trying to address these gaps through graduate programs, reskilling initiatives, and by leveraging the federal Jobs and Skills Australia workforce forecasts to target emerging shortagesapsc.gov.au.

- Vacancy and Fill Rates: Official APS-wide vacancy rates are not published, but some indicators show challenges in filling roles quickly. Long hiring times (as noted above) and competition for talent mean critical vacancies can remain open for extended periods, especially in ICT and regional postings. For context, in the Queensland Health department (outside the APS), dedicated recruitment drives brought nurse vacancies down to just 1.1% and doctor vacancies to 2.3% in 2024statements.qld.gov.au – highlighting that with the right strategies, public-sector roles can be filled. The APS is aiming for similar outcomes by using expedited hiring approaches (e.g. talent pools, streamlined vetting) for priority roles.

- Diversity and Niche Talent Initiatives: The APS has ongoing initiatives to attract First Nations talent, women in STEM, and people with disabilities. Indigenous representation in the APS is roughly 3.5% (approximately on par with the national Indigenous working-age population), but the government has set an ambitious target of 5% First Nations employment in the APS by 2030apsc.gov.au. Programs like the Indigenous Graduate Pathway and special measures roles are part of this push. Similarly, the APS is working to increase Indigenous senior leadership (aiming to nearly double First Nations SES officers by 2025)apsreform.gov.au. In niche areas such as cybersecurity and digital, new APS academies and communities of practice (e.g. the Digital Professions hub) are being used to both develop internal talent and brand the APS as an employer of choice for tech professionals.

Queensland Government

Queensland’s public sector – over 308,000 strong in 2024 – has been growing to meet service demands, with a focus on frontline rolespsc.qld.gov.au. The state’s talent acquisition efforts have shown success in expanding critical workforces, though some areas remain challenging:

- Workforce Size and Composition: As of March 2024, Queensland’s public service had 258,012 full-time equivalent (FTE) employees, up by ~11,700 FTE (+4.7%) from the previous yearabc.net.au. This surge is the largest annual increase in four years, driven mainly by investments in health, education, and public safety roles. Notably, 9 out of 10 Queensland public sector roles are frontline or frontline support positionspsc.qld.gov.au – reflecting the state’s emphasis on service delivery. In 2023–24, the health workforce grew by 6,546 FTE, and education by 513 FTE to keep pace with population needspsc.qld.gov.au. By contrast, corporate (back-office) roles, while a small share of staff, saw a resurgence: corporate services FTE grew 9.3% in a year (the fastest rate in years) after a pandemic-era hiring freeze in those areasabc.net.auabc.net.au. The government attributed this to a “right-sizing” of support roles that had been cut back in 2020–21abc.net.au. Still, frontline roles (teachers, nurses, police, etc.) remain the priority, comprising the vast majority of new hiresabc.net.au.

- Recruitment Successes: Queensland has actively tackled hard-to-fill roles with targeted recruitment campaigns. In healthcare and emergency services – occupations facing nationwide shortages – Qld achieved workforce increases of 5–7% in 2023–24themandarin.com.au. For example, ambulance officer numbers rose 5.64% over four years, closing in on parity with NSW’s larger ambulance workforcethemandarin.com.au. Doctor and nursing ranks also expanded (doctors +6.8%, nurses +5.2% over the year)abc.net.au. In policing, after concern about falling officer numbers, Qld ramped up recruitment: new police recruits nearly doubled from 284 to 558 in the year to March 2024abc.net.au. This has kept up with attrition and led to a net gain in officers by mid-2024abc.net.au. The pipeline of police applicants also grew dramatically – from 960 to 2,079 candidates in one yearthemandarin.com.au – thanks to incentives and advertising that improved the employer brand for QPS. These efforts indicate generally high fill-rates for priority roles; indeed, the Health Minister noted Queensland Health is now attracting enough candidates to bring nurse vacancy rates down to just ~1%statements.qld.gov.au, an extremely low level that suggests most nursing positions are being successfully filled. Such outcomes point to effective talent acquisition strategies in critical fields.

- Time-to-Hire and Process: Specific average time-to-fill metrics for the Queensland public sector are not published like NSW’s, but anecdotal indicators show improvements. Agencies have streamlined recruitment through initiatives like the centralized Smart Jobs portal and fast-track programs for graduates and interns. The Working for Queensland employee survey in 2023 found perceptions of recruitment fairness have improved, yet still over half of staff feel promotions and hiring lack clear criteriathemandarin.com.au. This suggests ongoing efforts to make hiring more transparent and merit-based (a key recommendation of the 2022 Coaldrake Review into Qld public sector culture). Moving forward, the new “Even Better Public Sector” strategy (2024–2028) emphasizes revamping recruitment and workforce planning, including timely reporting of workforce data (e.g. via the new State of the Sector report introduced in 2024)themandarin.com.au.

- Turnover and Retention: Overall turnover in Queensland’s public sector appears moderate, though it varies by agency. While a whole-of-sector attrition rate isn’t published for 2023, pockets of high turnover have drawn attention. For instance, the Queensland Police Service had an annual turnover of 10.7% in 2022–23abc.net.au, prompting retention initiatives (e.g. improved workloads and rural incentives). Health workforce attrition is comparatively low: nursing and midwifery saw about 6.1% attrition and doctors 4.3% in 2023–24statements.qld.gov.au – steady or improving from the prior year and roughly half the rate of NSW Health (where doctors and nurses turnover exceeded 10%)statements.qld.gov.au. Across Qld Health, attrition spiked to ~7% in the immediate pandemic year 2021–22 but has since settled down to pre-pandemic normsstatements.qld.gov.au. Low turnover in health roles is aided by initiatives like the Workforce Attraction Incentive Scheme, which targets regional and specialty shortagesstatements.qld.gov.au. In other sectors (e.g. education, administration), Qld has not flagged major retention crises; however, like many employers, it faces looming retirements (about 11% of Qld Health staff are over 60statements.qld.gov.au) and must plan to replace that cohort. The state’s high public-service growth suggests it is generally filling more positions than it loses, though ensuring new hires stay (especially in remote areas or high-stress jobs) remains a challenge.

- Skills Needs and Gaps: Queensland’s talent gaps mirror national trends in areas like health, STEM, and Indigenous services. Healthcare roles (doctors, nurses, allied health) remain in high demand – the government projects needing 45,000 more health workers by 2032, including nearly 6,000 additional doctors and 19,000 nurses/midwivesstatements.qld.gov.au. To meet digital transformation goals, Qld also competes for IT and data professionals, and for engineers and scientists (particularly in areas like environmental management or infrastructure). The Queensland Workforce Strategy 2022–2025 identifies digital literacy and cyber security as key skill priorities, as well as increasing the employment of First Nations peoples and people with disabilities. In terms of First Nations recruitment, Qld’s public sector has modest growth: Indigenous representation ticked up from 2.55% to 2.66% of employees in the past yearpsc.qld.gov.au. This remains below the 4% target (aligned roughly with Qld’s Indigenous population share) and indicates a gap in attracting/retaining Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander staff. Specialized programs (like identified roles in communities, Indigenous cadetships, and cultural capability training for managers) are being deployed to bridge this gap.

- Vacancies and Offers: Queensland now publishes workforce data annually, including vacancies in key services. As mentioned, vacancy rates in frontline health roles have fallen to very low levels in 2024 (around 1–2%)statements.qld.gov.au, which is a positive sign that funded positions are being filled. In policing and teaching, the government has acknowledged shortages but also reports progress (e.g. hundreds of teachers hired from interstate and overseas, and police academy intakes increased). The employment offer in Queensland’s public sector has been bolstered to attract talent: flexible work is widespread (in 2023, 92% of employees who sought flexible arrangements had them approvedpsc.qld.gov.au), and the sector promotes competitive benefits like additional leave, salary packaging, and relocation assistance for rural roles. Employer branding efforts – such as the “Join Queensland Health” and “Teach Queensland” campaigns – emphasize making a difference in communities, which resonates with mission-driven candidates. These factors, combined with a growing budget for workforce (the 2024–25 Qld Budget set aside over $1 billion for new frontline staffstatements.qld.gov.au), have generally strengthened Queensland’s talent acquisition outcomes. The main ongoing challenges are keeping pace with growth in demand (especially in health and human services) and continuing to improve internal hiring processes and perceptions of merit.

New South Wales Government

New South Wales has one of Australia’s largest public sector workforces and has recently focused on improving recruitment efficiency and managing high staff mobility. The latest data (2023) for NSW indicate notable trends in hiring speed, turnover rates, and workforce makeup:

- Workforce Size and Dynamics: NSW’s government sector employs roughly 430,000+ people (including public servants, health and education workers, etc.). This is about 10.3% of NSW’s employed populationpsc.nsw.gov.au, a proportion steady from 2022. After significant COVID-driven workforce expansions (especially in health), NSW’s public sector hiring continued at a brisk pace into 2023. There was a 12.9% increase in job openings across the NSW public service in 2023 (47,729 openings posted) compared to the previous yearpsc.nsw.gov.au. The largest recruitment needs were in Schools (education) – over 10,800 openings, general Education/Training roles (~6,800), Administration/Clerical (~4,868), and Emergency Services (~2,239)psc.nsw.gov.au. These figures highlight the high demand for teachers and health staff, as well as ongoing hiring in admin and frontline services. The influx of new employees was significant – the commencement rate (new non-casual hires as a % of workforce) rose to 12.2% in 2023, the highest since 2007psc.nsw.gov.au. This indicates that over one in ten NSW public sector employees were new to their agency that year, underscoring both growth and replacement hiring.

- Recruitment Speed and Processes: NSW has made strides in reducing time-to-hire. In 2023, the average time to fill a public sector job was 33.2 days, down by 5.5 days from 2022psc.nsw.gov.au. This continues a downward trend as agencies streamline recruitment stages. NSW’s average hiring time is now on par with private sector benchmarks (around 33 days) and significantly faster than some other governments. Factors aiding this efficiency include improved e-recruitment systems (the “I Work for NSW” jobs platform), proactive talent pooling, and possibly a sense of urgency in a “tightening labour market”psc.nsw.gov.au. However, it’s noted that data quality (completeness of recorded recruitment dates) can affect reported timespsc.nsw.gov.au. Nevertheless, the faster cycle times suggest NSW public service is adapting to avoid losing candidates – a critical move given competition with private employers. Additionally, the mobility within NSW agencies is robust: many openings are filled by internal candidates moving from one part of the sector to another. The government encourages this through streamlined transfer processes and policies that recognize service-wide experience. This internal mobility can shorten hiring times as well.

- Turnover and Attrition: The NSW public sector experienced elevated turnover in 2022, but saw some improvement in 2023. The separation rate (employees leaving their agency) fell from 13.4% in 2022 to 11.5% in 2023psc.nsw.gov.au. Likewise, the exit rate from the public sector (those leaving government employment entirely) declined from 11.1% to 9.2%psc.nsw.gov.au. These decreases suggest the wave of post-pandemic departures has somewhat abated. (Notably, 2022’s figures were skewed higher by events like the privatisation of a transport agency, which caused a one-off surge in exitspsc.nsw.gov.au.) Even at ~11.5%, NSW’s turnover remains higher than historical norms – reflecting a still-active job market. By service segment, turnover varies: NSW Health had around 13.2% separation (with nurses and doctors each over 10% attrition)statements.qld.gov.aupsc.nsw.gov.au, public schools had only ~7.3% (teachers tend to have longer tenure)psc.nsw.gov.au, police around 9.7%, and core public service departments ~13.9%psc.nsw.gov.au. This indicates retention is strongest in the education sector and more challenging in health and general administration. The median tenure of NSW public servants has fallen to 7.0 years – the lowest in a decade and a further sign of increased workforce fluiditypsc.nsw.gov.au. Many departures in 2022–23 were due to retirement (especially among age 65+ employees, who had an 18.7% exit rate)psc.nsw.gov.au, but a large number were mid-career exits as well, likely lured by other opportunities. To improve retention, NSW has initiatives like targeted pay raises in nursing, and programs to boost job satisfaction (the People Matter survey tracks engagement, indicating issues like workload and career development that are being addressed).

- Skills Needs and Critical Roles: NSW shares common high-demand areas such as healthcare, education, and technology. The state has been contending with a teacher shortage (hence the large number of school openings) and nurse shortages. Aggressive recruitment internationally and regionally for nurses and teachers has been underway. In digital and STEM fields, NSW has a sizable tech workforce and agencies like Service NSW and the Digital NSW team, but still must compete for talent in cybersecurity, data science, and IT project management. The government’s Digital Restart Fund and various tech modernisation projects have created roles that are sometimes hard to fill due to private sector competition. While the NSW PSC’s workforce report doesn’t list specific skill gap percentages in the snippet, anecdotal evidence shows ICT, engineering, and specialist regulatory roles can be difficult to recruit. NSW is also focusing on management and leadership capability, ensuring that as many senior bureaucrats from the baby-boomer generation retire, there is a pipeline of new leaders (the state runs leadership academies and talent programs to that end).

- Diversity and Inclusion – First Nations Focus: NSW has made notable progress in Indigenous employment. As of 2023, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people comprise 3.9% of the NSW public sectorpsc.nsw.gov.au, up from around 3.7% the year before. This exceeds the previous target of 3% and roughly equals or slightly exceeds Indigenous representation in the NSW working-age population. NSW’s Indigenous employment strategy set a goal of 1.8% representation in senior leadership, and although challenges remain (especially in higher pay grades), the overall increase is a positive trendpsc.nsw.gov.au. Culturally appropriate recruitment practices (like identified roles and Indigenous traineeships) have contributed. Alongside First Nations inclusion, NSW also surpassed its gender parity goal in the senior executive ranks (women hold about 41% of senior roles, continuing to rise) and is working toward targets in disability employment. These efforts in employer branding – positioning the NSW public service as diverse and inclusive – help widen the talent pool for hard-to-fill roles (e.g. attracting candidates to rural postings by emphasizing community impact and inclusive workplaces, which can resonate with First Nations candidates).

- Vacancies and Workforce Planning: NSW monitors vacancy rates in key sectors. As of mid-2023, NSW Health reported vacancies around 3–5% in various health professions, which was an improvement from earlier staff shortages (aided by recruitment of over 1,000 international nurses in 2022–23, for example). The public education system similarly has been trying to reduce its vacancy rate (particularly in rural schools). The state’s approach to workforce planning includes hiring cadets and graduates (through programs like Teach NSW scholarships, nurse graduate intake guarantees, etc.) to build future supply. Additionally, NSW has been willing to adjust employment offers – for instance, offering hiring bonuses or higher wages for some hard-to-recruit professions (such as midwives and paramedics) in response to competition. Employer branding under the tagline “Make NSW Great” (used in some recruitment materials) focuses on the scale and impact of state projects (for example, building infrastructure, protecting communities, etc.) to attract mission-oriented talent. With a new government in 2023, there are also renewed commitments to public sector growth in frontline areas (police, health) and potential restraint in bureaucracy growth, all of which will shape recruitment and workforce performance in the coming year.

Victorian Government

Victoria’s public sector has experienced significant growth in recent years, particularly in frontline services, but is now entering a period of fiscal constraint. Current data highlights both strong recruitment outcomes in key areas and upcoming challenges as the government seeks to reduce headcount:

- Workforce Size and Recent Growth: The Victorian public sector (including public service, education, health, police, etc.) reached over 382,000 employees as of June 2023themandarin.com.au. This represented a 4.1% increase (about +12,450 FTE) from the previous yearthemandarin.com.au – a sizeable expansion, accounting for roughly half of all new jobs in Victoria that year. Growth was concentrated in frontline roles: about 41% of Vic public sector staff work in healthcare and 26% in government schoolsthemandarin.com.au, and these sectors drove most of the hiring. In fact, VPSC (Victorian Public Sector Commission) data shows back-office “administrative” roles actually fell by 1.1% over the yearthemandarin.com.au, indicating deliberate restraint or cuts in corporate areas while bolstering frontline capacity. This aligns with government policy to prioritize service delivery roles (nurses, teachers, child protection, etc.) over support roles.

- Recruitment and Mobility: In 2022–23, Victoria onboarded an enormous number of new staff. There were 61,051 non-casual new starters in the Vic public sector that yearvpsc.vic.gov.au – which means roughly 16% of the workforce started fresh (many filling newly created positions in health/education). Simultaneously, 50,498 non-casual employees separated from a public sector employervpsc.vic.gov.au, implying a high turnover volume, though not all separations mean leaving government entirely (some move between agencies). Within the core Victorian Public Service (VPS) – the departments and agencies comprising the bureaucracy – there were 12,816 new hires and 12,571 separations in 2022–23vpsc.vic.gov.au. A notable feature in Victoria is the Jobs and Skills Exchange (JSE), introduced in 2019 to facilitate internal transfers and promotions across the VPS. Thanks to the JSE and a common recruitment policy, internal mobility has increased – the number of employees transferring between VPS organizations grew from about 1,175 pre-JSE to 2,833 in 2023vpsc.vic.gov.au, roughly 5% of VPS staff moving internallyvpsc.vic.gov.au. This means many vacancies are filled by existing public servants (shortening recruitment time and retaining expertise within government). For external recruitment, Victoria’s processes are traditional but the scale of hiring (especially in health and education) has led to ongoing recruitment campaigns (e.g. international recruitment for nurses, incentives for regional teachers). Time-to-hire metrics aren’t published in the VPSC public reports, but large recruitment programs (like for nurses) have been executed relatively quickly through bulk recruitment rounds. Nonetheless, administrative hiring can still be multi-stage and take a couple of months on average, similar to other public services.

- Turnover and Retention: With over 50k separations in a year, Victoria’s turnover rate is estimated to be in the low teens (approximately 13% of non-casual staff left their employer in 2022–23). This is comparable to NSW’s 11.5% and just under the national all-sector average (~14%). The high number of exits partly reflects the size of the workforce and normal retirements, but also a dynamic job market. According to VPSC data, separation rates fell in most industry segments in 2023 compared to the previous yearvpsc.vic.gov.au – meaning retention slightly improved post-pandemic. However, there were increases in turnover in specific areas like the Emergency Services Telecommunications Authority and water management agenciesvpsc.vic.gov.au, showing some localized challenges. The Victorian government has expressed that it wants to maintain a strong frontline while trimming the overall public service – this implies managing attrition smartly. Indeed, 2023 saw the first signs of downsizing: by late 2024 and into 2025, the government instituted a partial hiring freeze and targeted reductions in the core public service. In February 2025 an independent review was announced to cut 5–6% of VPS jobs (roughly 3,000 positions) to help address budget deficitsthemandarin.com.autheguardian.com. Early indications are that natural attrition will be used where possible (e.g. not backfilling some departures) and that duplication and inefficiencies will be identified for job cutsthemandarin.com.au. This shift means Victoria’s previously rapid workforce growth is likely to slow or reverse in the short term. Retention of crucial talent becomes even more important in a contraction scenario – the government will aim to hold on to nurses, teachers, and other critical staff while shedding lower-priority roles. Morale and employer reputation could be tested during this downsizing, so Victoria will need to manage it carefully to avoid a talent exodus or drop in engagement.

- Skills and Talent Gaps: Victoria faces similar skill shortages as other jurisdictions. The healthcare and social services workforce has been a major focus (with large investments to train and recruit clinicians). Still, shortages persist in areas like regional healthcare, certain medical specialties, and mental health practitioners. STEM skills are also in high demand: the public sector seeks data analysts, digital service designers, and engineers (especially for Victoria’s big infrastructure projects) – competition with the private sector for these professionals is intense. For example, the VPSC noted that occupations in science and technical fields have among the higher vacancy and turnover rates (though exact stats aren’t cited here). Another niche need is child protection and family services workers, where turnover historically has been high due to job stress – the government has put in place scholarships and pay boosts to attract more graduates to this field. On the technology front, the Victorian government has established a Digital Victoria strategy and is recruiting heavily for IT roles to support cybersecurity and digital service delivery (like Service Victoria). First Nations employment in the Victorian public sector is an area of progress: Indigenous staff make up about 1.2% of the overall public sector workforce (excluding schools)vpsc.vic.gov.au, roughly equal to Indigenous peoples 1% share of Victoria’s population (noting Victoria has a smaller Indigenous population proportion than many other states). In the core VPS, Aboriginal employment was likewise ~1.2% in 2022genderequalitycommission.vic.gov.au. While this suggests proportional representation at the aggregate level, the government has initiatives to increase that figure further and to improve Indigenous representation in senior roles. The Barring Djinang program, for example, is a long-running strategy to support Aboriginal career development in the Vic public sector.

- Workforce Planning and Employment Offer: Victoria’s approach to workforce planning has been under scrutiny. A recent Auditor-General report (2023) on Building a High-Performing Public Service found that while agencies have many frameworks and strategies, the central oversight of capability-building could be strongeraudit.vic.gov.auaudit.vic.gov.au. The state has multiple programs to boost capability: from graduate recruitment (the VPS Graduate Program is highly competitive, bringing in hundreds of graduates annually) to targeted training for existing employees. The employment value proposition in Victoria’s public sector has traditionally included generous conditions (e.g. flexible work arrangements, salary progression within bands, and extensive leave entitlements). Post-pandemic, flexible and remote work have become standard in many departments, which helps attract talent – though the government also encourages a balance to maintain service delivery. A challenge for Victoria now is managing its employer branding during budget cuts. After years of expanding services and emphasizing the public sector as a growth employer, the narrative is shifting to efficiency. The Premier and public service leaders stress that even with cuts, the focus remains on “delivering value for money and being transparent about performance”themandarin.com.au. In practical terms, this means Vic may impose stricter hiring controls (only critical roles approved) and ask agencies to justify recruitment in context of workforce plans. Vacancy levels in non-frontline roles might intentionally rise as positions are left unfilled to meet savings targets. On the other hand, essential services (health, education, police) are generally shielded from cuts – recent data even showed frontline shares of the workforce increasing relative to corporate rolesthemandarin.com.au. Therefore, talent acquisition in Victoria will likely become more selective: focusing on priority areas and niche skills, while overall recruitment volume could drop from the highs of the past two years.

Sources: Recent government workforce reports and data have informed this analysis, including the Australian Public Service State of the Service Report 2022–23 apsc.gov.auapsc.gov.au, Queensland’s State of the Sector 2024 data releaseabc.net.auabc.net.au, the NSW PSC Workforce Profile 2023psc.nsw.gov.aupsc.nsw.gov.au, Victoria’s State of the Public Sector Report 2023 (VPSC)themandarin.com.au, and various auditor-general and media insights for contextstatements.qld.gov.authemandarin.com.au. Comparisons to private sector benchmarks use Australian HR Institute survey data and ABS statisticsapsc.gov.auahri.com.au. These sources underscore both the progress and challenges in public sector talent acquisition as of 2024–2025.